The sociology of Love Island via Bourdieu

I am struggling with writing this summer and am now forcing myself to write blogs when I get stuck writing the ‘real’ academic work. So here’s the first output of my new summer routine — a Bourdieusian analysis of Love Island. Love Island is particularly useful to demonstrate Bourdieu’s concepts — particularly because questions of taste and social class are the dominant themes that come from Bourdieu’s work and that Love Island and those who watch it are often ridiculed for a lack of taste.

Bourdieu’s concept of field argues that individuals are engaged in struggles in a number of (relatively) autonomous social spaces to increase possession of varieties and volumes of capital. Love Island almost literally organises individuals into a (relatively) autonomous social space with contestants encouraged to increase the volume of their social relationships with the end goal of finding love and/or £50,000.

In Bourdieu’s work, different fields are governed by different capitals and different rules — the artistic field for example is governed by rules that reject or deny money and a fight for cultural capital and legitimacy. Within Love Island, though money on the ‘outside’ is never far away from the equation — you can see that the villa is governed by different forms of capital and rules.

Within Love Island, the dominant form of capital is, perhaps obviously, social capital. The participants in the game show need to get into relationships — both friendships that will help them (what Anton goes on about when he talks about what people ‘bring to the villa’) and, most importantly, romantic relationships which, well, can help you find love and/or £50,000.

But not all social capital works the same way — viewers act as (cultural) intermediaries to assess the ‘disinterestedness’ of the relationships. When Bourdieu talks about art, he uses the term disinterestedness (via Kant) to talk about how artists need to demonstrate a lack of concern about money in order to prove their artistic merit. Likewise, in Love Island, the disinterest in ‘game playing’ and the ‘outside’ – where they might convert their fame into fortune – is a key part of the ways we view the relationships. Game playing is policed within the villa — with Molly-Mae’s earlier lack of decision on coupling giving the perception she was keeping her options open, and thus playing games to, well, win the game:

If participants’ relationships seem genuine — say, like Tommy and Molly-Mae’s relationship is now possibly seen, or Dani and Jack from last year — then they are seen as legitimate and their social capital takes the form of symbolic capital. Symbolic capital in Bourdieu’s formulation refers to:

“any property (any form of capital whether physical, economic, cultural or social) when it is perceived by social agents endowed with categories of perception, which cause them to know it and to recognize it, to give it value.” (Bourdieu, 1998: 47).

Genuine relationships then are rewarded with symbolic capital by the viewers as seen by the more popular, genuine couples being saved from elimination. Such is the cynicism with which people’s actions in the villa are scrutinised, when Amy — characterised as clingy or fame hungry or any number of gendered stereotypes — left the villa to give herself space, the social media reaction suggested that maybe Amy had been ‘disinterested’ in money and the ‘outside world’ after all! The debates about intention and genuineness are not uncommon to using Bourdieu’s social theory either — many writers have suggested that Bourdieu’s work has a very instrumental and cynical look at social life with individuals only interested in getting more capital (see Jenkins, 2002 or Sayer, 2005 for debates).

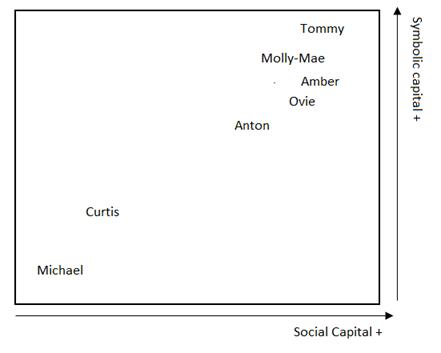

Within Bourdieu’s work, you can map the positions of individuals into these fields based on their possession and volumes of capital. You can of course judge yourself on the positions — and I left out a lot of people, partly because I forget names and partly because I’m only illustrating — but I based it roughly on the last elimination week and the types of relationship they are in. Tommy and Molly-Mae are arguably the most popular romantic couple, Amber and Ovie are two of the most popular contestants but are in a platonic/placeholding relationship while Anton seems to be one of the more popular people in the villa and in a relatively new relationship with Belle. Curtis and Michael I put near the bottom because they are terrible people.

The villa as social field

The villa as social field

The cynical view towards people’s actions in the villa only takes us so far in because the participants do act in ways that are contrary to their interests. The ‘rules of the game’ — or what Bourdieu would call ‘doxa’ — operate differently, with a much less ‘instrumental’ way of operating. Love Island operates in its own way with a certain honour code that participants mostly follow. Eliminations demonstrate this best, with participants being given ‘second chances’ even when eliminating stronger or more popular participants might give your couple a better chance at winning. Same with the couples themselves: being a better, genuine couple who have the potential to win the programme tends to help avoid elimination by your fellow islanders! And indeed, platonic friendship as much as romantic relationships can help keep you in the villa — despite, well, the ‘love’ part of the game. If you want an insight into how the rules of the game operate — or the honour code of the villa — then just listen to Anton’s monologues during eliminations:

‘The Outside World’

The ‘autonomous’ social fields we talk about with Bourdieu is quite helpful to talk about how social fields work in different ways with different rules and with different stakes (capitals). But ultimately fields are ‘relatively’ autonomous and can act in ‘ homology’ with other social fields — such as more economic or socially powerful fields. So while gaining social capital and building ‘genuine’ relationships form the basis of the competition in the villa, these activities are ultimately directed elsewhere. The hope for these participants is that they can convert their symbolic capital — or ‘genuine’ social capital — into more powerful forms of social capital or gain access to economic capital.

It is important to note that the ‘outside’ ultimately determines who goes into the villa, and to get into the villa you need forms of social capital to begin with. The need to have a certain social media following in order to be selected during the audition process leads to some debate about how real or fake the competition in the villa is. The participants are ultimately archetypes of what Brooke Erin Duffy would call ‘aspirational labour’. The prevalence of modelling and social media influencers in the the jobs prior to coming into the villa are no coincidence, nor is the likely career paths that these participants will try to follow once leaving the villa. But as research into aspirational labour shows, the success in being a social media star often relies on access to forms of capital — whether that is money, taste or social relationships. The fact that ‘shocks’ such as ex-partners entering the villa or messages on Instagram is also not likely a coincidence, but a result of the close social circle these people operate within or the relationships (or celebrity) they can draw upon prior to the villa(Danny Dyer’s daughter, AJ/Tyson Fury’s brother).

That’s my sociological take on Love Island — no one asked for it and no one needed it. Looking forward to boring my students next year for two hours with a lecture on this topic.