Again, I have another blog published, this time with the Sociological Review’s Solidarity and Care project. The blog, which talks about our relationship with plants during Covid, is part of some writing I’m doing on the subject of plants, labour and care.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

The cultural politics of Arsene Wenger

Here’s a link to a blog I wrote a few months ago about my ongoing project into the ‘cultural politics’ of Arsene Wenger. I’ve reposted it here for those who can’t access it:

Of all the topics I had thought I would dedicate several months of thought, research and writing when I started at univeristy, I didn’t imagine Arsene Wenger would be one of them. Here I am however, in the process of beginning to produce some output from this passion project – a process which began at the Football Collective Conference in Sheffield last month. In terms of my academic career, my main concerns are the links between culture and economy as well as the relationship between work and commerce, particularly in the creative/cultural industries. Football in particular interests me – both as a fan and a researcher – because it represents an especially acute relationship between the work of footballers and money. The near exponential growth in television revenue, corporate and state sponsorship of the sport internationally has had a profound effect on the sport in the last few decades. I have spoken on my ideas around football previously in an attempt to talk about the ‘symbolic’ work of football – the romance, the stories, the myths, the value of aesthetic football – and how this links into wider social fields. The research I’m doing on Arsene Wenger is not necessarily about Arsene Wenger alone but rather how his tenure at Arsenal links into the myths surrounding the ‘beautiful game’ but also these profound changes in football we have witnessed.

This project initially started out as a paper idea to extend out Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of the Don Quixote effect (more on this later) into a more literal interpretation of Arsene Wenger as Don Quixote. This idea was at the end of 2017 when I started writing and obviously a great deal has changed since then, not least that Arsenal actually sacked Wenger at the end of that season. The project’s methodology is inspired by the David Bowie Five Years documentary and aims to reconstruct the representations of Wenger in the news media over what I consider four key seasons in his career. I’ve chosen to focus on his Arrival (1996/97), Invincibles season (2003/04), ‘Revival’ (2013/14) and Departure (2017/18) because they can tell us something sociologically interesting about the wider social fields and social space. Certainly, so far, I have found three key themes that have emerged from the study so far: the relationship between Arsene Wenger and multiculturalism in England; Wenger’s relationship between football as art or commerce; and finally, the notion of Wenger as a romantic figure ‘out of time’ with modern football.

Is it a coincidence that Arsene Wenger arrives in English football after a summer semi-final for England with the song Three Lions at number one and then leaves before a summer semi-final for England with the song Three Lions at number one? Probably. Yet, the relationship between that song and the ‘common sense’ of English football I feel is pertinent to Wenger’s arrival and departure. The melancholic story of a team of faded glory whose day might come again after 30 years, 40 years, 50 years of hurt. It is not however only the story of faded glory of a national football team that is important here: while the partially ironic chants of “it’s coming home” dominated the summer of 2018, it is within the wider context of Brexit Britain that this occurs. Likewise, the chants on the football terraces are have not historically been simply about the World Cup win against Germany but of “two world wars and one world cup”. This is a postcolonial melancholia.

Wenger, or at least the media portrayals of him, represents both sides of the society Paul Gilroy observes in his book After Empire – from the celebration of multiculturalism and the potential of modernising the English game, to the ‘Sam Allardici’ resentment of the English management class. Wenger arrives to England as the archetypal ‘stranger’ in Georg Simmel’s sense – the figure who comes today and stays tomorrow. The obvious way to look at this ‘strangeness’ is the now infamous news headline ‘Arsene Who?’ Yet, it is a contradictory notion of foreignness. Wenger represents a stranger that has something to teach the English coach, but by the same token distances him from English coaches.

‘If Wenger makes a go of things, then more foreign coaches will surely follow him here. Speaking another language does not necessarily make a man a potential genius as a manager but English football has missed out by not being part of the European coaching circuit. The domestic game needs to share the spread of ideas as well as offering opinions of its own.’ (Lacey, 1996)

As the analysis of this project will show, Wenger represents a form of ‘exotic cultural capital’ – containing a multicultural (and educated) form of capital that both provokes admiration – his knowledge is later appropriated and then usurped within the game – but also ridicule. It is also a form of cultural capital though that is exotic because it represents a ‘bit of the Other’ (to quote Stuart Hall) but only within the bounds of whiteness.

The crux of my project is on this notion of the ‘Don Quixote effect’, borrowed from Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu (1984) uses the term to describe individuals that have ‘outdated’ dispositions, where the habitus of individuals no longer fits with the social space which originally formed them. To borrow form competitive strategy analogies, Arsene Wenger’s coaching became the ‘benchmark’ and like all benchmarking strategies, it results in emulation and nullification of the original strategic advantage. The Invincibles, arguably the peak of Wenger’s powers, saw Arsenal become the first team to complete a 38-match season unbeaten in English football (the mighty PNE though remain unbeaten through an entire domestic season). Yet, even while Wenger was reaching the height of his achievement the wider social field of English football was undergoing a fundamental change. Chelsea, now under the ownership of billionaire Roman Abramovich, were tinkering their way through the Champions League after buying their way through the international transfer market. The changes in the transfer market wrought by Chelsea ultimately would result in a rationalisation of the English Premiership. These changes would place the field in a position even more orientated toward economic capital but already operating with the innovations Wenger introduced to English football as near minimum requirements.

The intervening years between that Invincibles season and the 2014 FA Cup win were occupied with discussions of how miserly Wenger and the Arsenal board were and how investment in a new stadium had hampered the team’s ability to compete. Yet, Wenger, ultimately, has never been someone to submit to the logic of economic capital. A recurrent theme of the media analysis is how averse to spending Wenger has been throughout his tenure.

‘There are very few people worth pounds 10m and I’m not sure I could envisage paying that sort of money for one player.’ (Wenger, cited in Walters, 1996)

It is here that the reference to a ‘Don Quixote effect’ is more literal than simply a set of outdated dispositions in a changed social field. Wenger is the romantic figure, the chivalrous knight from more honourable times trying to return football to these glory times. Wenger’s values throughout football reflect the idea of football as the ‘beautiful game’ played well with a focus on developing young players – values that never changed even when money was spent on the likes of Özil and Sanchez. As Wenger himself says, he aspires to producing football that is as close to art as possible:

I believe the target of anything in life should be to do it so well that it becomes an art. When you read some books they are fantastic, the writer touches something in you that you know you would not have brought out of yourself. He makes you discover something interesting in your life. If you are living like an animal, what is the point of living? What makes daily life interesting is that we try to transform it to something that is close to art. And football is like that. When I watch Barcelona, it is art. (Wenger, 2009)

There is also something in exploring the novel itself too – the Don Quixote story represents both a comedy and a tragedy. This tragicomic feeling reflects much of the media representations of Wenger’s later years at Arsenal, with the ridicule towards Wenger’s methods and approach becoming a recurrent trope in the media. The ‘Wenger Out’ discourse was often predicated on the belief that Wenger was no longer in tune with modern football.

There is a lot of work to be done on this project before I manage to get it out for publication in some form or another, but as I say it is not simply a project about Arsene Wenger. It is about using Arsene Wenger’s relationship with a changing English game to explore the profound changes in football and the nation. Indeed, there is also a final contradiction that I aim to explore further in this project: Wenger, the knight yearning for more honourable times falling ‘out of time’ with a country itself yearning for more glorious times.

In ‘no man’s land’? Dentistry and Covid-19

In ‘no man’s land’? Dentistry and Covid-19

One of the projects I’ve been investing a lot of (belated due to several job changes) work into has been our project we did a couple of years ago into the work of dentists. Along with a colleague, we got a small amount of funding to investigate the rising levels of stress within Scottish dentistry. The profession’s key journal — the British Dental Journal — has been rife in recent years with articles showing concern and investigations into the high levels of stress and burnout in the profession. Our study attempted to investigate this problem but from a more sociological viewpoint, focusing on the experience of work and institutional arrangements within Scottish dentistry.

Our research — which is in the last stages of finally being written up — aimed to explore the reported intensification of dentists’ work, the regulation and governance of dental work, and the emotional and physical demands of their work. Obviously, a couple of years has separated our interviews and the current Covid-19 crisis. Yet, the coronavirus pandemic presents a crisis that accentuates many of the existing tensions within dentistry. Dentistry is one of the professions most exposed to the virus itself as well as one of the key professions that will fall through the cracks of the government’s provisions for workers in this country. Although this is written from the perspective of Scottish dentistry — because of its devolved payment setup — the tensions identified in dental provision during this pandemic substantially overlap with dental care more widely in the UK.

As a profession, dentistry represents an exemplary form of ‘body work’ (Cohen ,2011; Twigg et al. 2011; Wolkowitz, 2002)– a type of labour that is primarily directed on the bodies of others. Various jobs within health care more widely, the beauty industries and the care sector depend on the assessment, handling and manipulation of patients’ or customers’ bodies as part of the work. Dentists’ work is typical of the demands of ‘body work’ with their jobs demanding ‘co-presence’ — the work cannot be done away from the patient — requiring intensive one-to-one time, a great deal of face-to-face interaction — and emotional reassurance — and a form of work that requires demanding dexterous forms of labour. In our research, this work has been found to be both emotionally and physically demanding. Dentists are engaged in a form of health care that has several phobias attached to it, their work that involves a lot of physical manipulation that puts a lot of pressure on their own bodies, in addition to being subject to more ‘aesthetic’ or customer-focused demands.

Importantly, the work performed on patients by dentists deals with a lot of bodily fluids, and many of the procedures are themselves ‘aerosol’ generating — just think of the amount of fluid and suction required in many standard dental treatments. ‘Aerosol generating’ is a particular red flag in regard to the coronavirus, with the spread of the virus linked to droplets emitted from the nose and mouth. The problems with performing dentistry during this pandemic is perhaps illustrated in recent charts that showed dentists to be the most at-risk form of work for catching the coronavirus. Guidance for dentists in these times has been mixed with some dentists bemoaning the responsiveness of their governing institutions during this fast changing crisis. Dentistry has been largely treated as a non-essential form of health care and the response has generally downgraded dental treatment from the list of priorities. Dentists were advised within Scotland on the 23rd March to cease all routine dental treatment, with England’s similar guidance arriving on the 25th March. The result is that all urgent, emergency case work is now performed by the wholly salaried dental workforce within the NHS.

Yet, the problems with the pandemic for the work of dentists cannot be limited to the particularities of the dental treatment itself. One of the key themes that emerges in our research — and previous research on dentistry — is the apparent conflict between ‘knights’ and ‘knaves’ or care and commerce. This is not necessarily unique to dentistry itself, but is accentuated by the dental treatment being one of the few areas of health care not wholly covered by the NHS. Annemarie Mol’s (2008) work, which developed the notions of a ‘logic of care’ and a ‘logic of choice’ through her study of the treatment of diabetes in Holland, is particularly pertinent to the study of dentistry. Scottish dentistry — and dentistry more widely in the UK — arguably operates within a ‘logic of choice’ where the provision of dentistry is effectively ‘outsourced’ by the NHS to general practices — in Scotland this treatment is partly subsidised — and patients can be offered various private solutions that supplement the basic NHS treatments available. Most dentists regard themselves as operating from within a ‘logic of care’, where relationships with patients and developing ‘continuity of care’ is the ultimate goal of their work. Yet, as our research has found, dentists themselves feel a particular tension between this logic of choice and their own belief in a logic of care.

The relevance of our research and key problem for dentistry during this coronavirus pandemic is being stuck in between these two logics. The operation of this ‘logic of choice’ ultimately leaves dentists particularly exposed to the current crisis: not sufficiently within the ‘care’ setting to have this work protected centrally as part of the NHS and not sufficiently within the market setting to gain full protections for their work. Dentists are for the most part self-employed and with the closing down of most face-to-face business in the UK— non-essential retail jobs, beauty industry business, restaurant trade — as a result of the crisis, we’ve seen a drop in economic activity and a rise in unemployment unprecedented in both severity and speed. The response of governments worldwide has been to, quickly, work to guarantee the jobs of individuals made unemployed by the crisis. As we’ve seen from the multiple budgets and additional measures Rishi Sunak has had to create, each government response has covered numerous affected groups but left a number of others exposed to substantial drops in their income. The largest group that many felt had to wait too long for government help was the self-employed. Eventually, last Wednesday, the government announced a number of protections for the self-employees. Yet these provisions have been capped and people earning over £50,000 are not eligible to claim — even to the capped amount — leaving many dentists facing months without income, and those that are eligible will have to wait until the end of June to see these incomes.

Dentistry has been treated as something of a luxury in this time of crisis. Indeed, this belief in ‘knights’ and ‘knaves’ too has an effect — in our research, dentists sometimes felt that patients saw their advice for treatments often being seen as ‘upselling’ rather than the advice of health care professionals. It is sometimes hard to make a case to support a profession that a number of people are afraid of or are perceived as particularly well off — especially with the news that many earn above this £50,000 threshold — yet, dentists will be part of the NHS’s response to the crisis. Already public service dentists in the NHS are taking over much of the urgent dental care of those currently suffering from Covid-19 and the redeployment of these dentists into other roles within the hospital system is being discussed and implemented. General practice dentists — whose doors have largely been closed to the public and currently working without income — are already part of the triage system, with dentists answering their practices phones and assessing whether these cases need escalating to the public dental service. Soon, these general practice dentists will be asked to volunteer in the service to treat urgent cases. In Scotland, other health services which exist with similar tensions between public and private provision, such as pharmaceutical and optical services will continue to receive 100% of NHS funding. It is notable that the initial offer for dentists was to back only 90% of this funding (that is 90% of the 20% the NHS subsidise for treatments – the remaining 80% being the upfront cost for patients).

The problem is what happens after the crisis. Although many nurses and some dentists will be able to claim state support, a substantial part of the sector will not. As the BDA has noted, many of these measures will not help associate dentists or those who run practices. Within the Scottish news it has recently been reported that practice owners worry that dental provision in the country will be ‘decimated’ with many businesses potentially unable to see themselves through the crisis. Although yesterday new measures were put in place to cover up to 80% of average item and patient income in Scotland, many practices are dependent on the balance between private income to cover the public service work they perform. Our own research has found that price freezes on item lists over the past years of austerity in Scotland have led to increased intensification of dental work in order to maintain income levels — what effect this crisis and the government response has to dentists working lives and the value of dental care in our country is an urgent question.

A sociology of the buddleia — and everyday ecological resistance

A sociology of the buddleia — and everyday ecological resistance

I recently got a buddleia plant, ostensibly because it is a butterfly friendly plant but mainly because it looks bloody marvellous. Buddleia are fascinating plants. They are overwhelmingly popular with amateur gardeners because of their insect friendly properties, their fantastic honey smell and their colourful but somewhat dishevelled appearance — the ecological equivalent of an un-ironed shirt. They are also a plant that is seen an invasive foreign species, that spreads widely and often occupies derelict spaces — such as canal sides, building sites and especially the railways. Though still popular with gardeners as part of their usefulness to butterfly revival, DEFRA treats them as invasive and gardeners should be careful to avoid their spread.

As a result of my gardening habit, I’m quite the garden watcher now. My journey to work will see me leave my dwarf sugar plum buddleia and a number of other garden varieties in Glasgow and then via a railway journey to Edinburgh hundreds of plants of the wild, invasive variety.

Part of this garden spotting sees me eyeing up other gardens too when out for walks. One of the things I see quite often — in addition to buddleias — are configurations of rosemary, lavender, heather, foxgloves and others which are often planted together in fairly small gardens. While some of these plants are particularly bonny, they are not natural fits or the most beautiful plants you could put together — there are reasons for them to be put together. As someone who walks to clear my head and think through ideas, it is no coincidence that I start thinking sociologically about these gardens. With the ongoing ecological and climate crises — more widely, the news of insect depopulation but more specifically, the downturn in numbers of bees and butterflies — a lot of advocacy from nature groups has gone out to individual gardeners on how different plants can make a difference.

A friend recently recommended I read Tsing’s (2015) ethnography The Mushroom at the End of the World. I must admit, I’m a life-in-capitalist-ruins kind of guy these days anyway. What Tsing talks about here is how the Matsutake mushroom — highly prized in Japanese cuisine — emerges or thrives in forests that have been disrupted by human activity, such as logging, and how this fits into a global chain of commerce. This book I started after finishing our pilot study into crofting in Scotland, where one of the key things to come out of this project too was the complicated relationship between nature, human development and notions of ‘care’. For crofters, maintaining a croft so that nature didn’t run wild was seen as natural. Here, gardeners put these ‘artificial’ configurations together — the buddleia itself comes originally from China — as ways to help and restore nature.

The configurations of rosemary, lavender and buddleias are not a million miles away from matsutake’s emergence from human activity. For me, these represent a form of ‘assemblage’ — not just the very specific ‘assembly’ or configuration of the plants, but the material plants themselves, the human labour that has gone into planting them, the discourses surrounding ‘butterfly/bee friendly’ plants and ‘doing our bit’ and a number of other social practices — that could be seen as a form of everyday resistance to climate and ecological crisis. While perhaps more discursively produced in a sense, they are also a little bit hopeful too. In such a hopeless time of climate emergency, I cling on to any elements of resistance. It would be easy to see these configurations of plants as another form of governmentality in these neoliberal times — making us responsible for addressing these ecological crises through responsible gardening. There certainly is an element of that. But for me they are invitations. Obviously they are literal invitations to animals for food, but also invitations to act and hope for a solution to our ecological troubles. They act as non-instrumental gifts to nature that, while acknowledging our place within the cycle, do not come with recognition of this labour. Much of this work goes unrecognised — except for the odd garden fan who knows the recommended plants list — and depends on a cycle between paid employment and consumption, which obviously is classed too. Also, while some of the plants are particularly bonny, some are darn right dull in a garden (I’m looking at you rosemary).

These are the initial thoughts I’m playing with anyway, it is a direction of travel that I plan to read and write a great deal more about in future. I’ve certainly collected quite the amount of literature to properly engage with discussions around social (re)production and care, probably as a form of summer procrastination. But I also hope this will occupy my thoughts further when I come to next flowering season and walk to see what new configurations exist or where the next buddleia will emerge from on my next walk.

The sociology of Love Island via Bourdieu

The sociology of Love Island via Bourdieu

I am struggling with writing this summer and am now forcing myself to write blogs when I get stuck writing the ‘real’ academic work. So here’s the first output of my new summer routine — a Bourdieusian analysis of Love Island. Love Island is particularly useful to demonstrate Bourdieu’s concepts — particularly because questions of taste and social class are the dominant themes that come from Bourdieu’s work and that Love Island and those who watch it are often ridiculed for a lack of taste.

Bourdieu’s concept of field argues that individuals are engaged in struggles in a number of (relatively) autonomous social spaces to increase possession of varieties and volumes of capital. Love Island almost literally organises individuals into a (relatively) autonomous social space with contestants encouraged to increase the volume of their social relationships with the end goal of finding love and/or £50,000.

In Bourdieu’s work, different fields are governed by different capitals and different rules — the artistic field for example is governed by rules that reject or deny money and a fight for cultural capital and legitimacy. Within Love Island, though money on the ‘outside’ is never far away from the equation — you can see that the villa is governed by different forms of capital and rules.

Within Love Island, the dominant form of capital is, perhaps obviously, social capital. The participants in the game show need to get into relationships — both friendships that will help them (what Anton goes on about when he talks about what people ‘bring to the villa’) and, most importantly, romantic relationships which, well, can help you find love and/or £50,000.

But not all social capital works the same way — viewers act as (cultural) intermediaries to assess the ‘disinterestedness’ of the relationships. When Bourdieu talks about art, he uses the term disinterestedness (via Kant) to talk about how artists need to demonstrate a lack of concern about money in order to prove their artistic merit. Likewise, in Love Island, the disinterest in ‘game playing’ and the ‘outside’ – where they might convert their fame into fortune – is a key part of the ways we view the relationships. Game playing is policed within the villa — with Molly-Mae’s earlier lack of decision on coupling giving the perception she was keeping her options open, and thus playing games to, well, win the game:

If participants’ relationships seem genuine — say, like Tommy and Molly-Mae’s relationship is now possibly seen, or Dani and Jack from last year — then they are seen as legitimate and their social capital takes the form of symbolic capital. Symbolic capital in Bourdieu’s formulation refers to:

“any property (any form of capital whether physical, economic, cultural or social) when it is perceived by social agents endowed with categories of perception, which cause them to know it and to recognize it, to give it value.” (Bourdieu, 1998: 47).

Genuine relationships then are rewarded with symbolic capital by the viewers as seen by the more popular, genuine couples being saved from elimination. Such is the cynicism with which people’s actions in the villa are scrutinised, when Amy — characterised as clingy or fame hungry or any number of gendered stereotypes — left the villa to give herself space, the social media reaction suggested that maybe Amy had been ‘disinterested’ in money and the ‘outside world’ after all! The debates about intention and genuineness are not uncommon to using Bourdieu’s social theory either — many writers have suggested that Bourdieu’s work has a very instrumental and cynical look at social life with individuals only interested in getting more capital (see Jenkins, 2002 or Sayer, 2005 for debates).

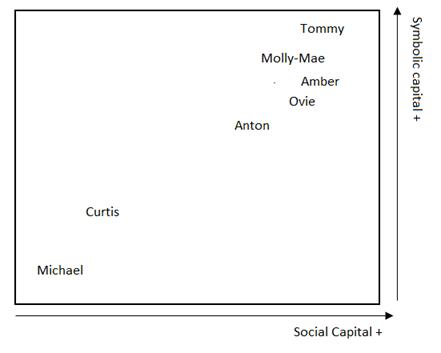

Within Bourdieu’s work, you can map the positions of individuals into these fields based on their possession and volumes of capital. You can of course judge yourself on the positions — and I left out a lot of people, partly because I forget names and partly because I’m only illustrating — but I based it roughly on the last elimination week and the types of relationship they are in. Tommy and Molly-Mae are arguably the most popular romantic couple, Amber and Ovie are two of the most popular contestants but are in a platonic/placeholding relationship while Anton seems to be one of the more popular people in the villa and in a relatively new relationship with Belle. Curtis and Michael I put near the bottom because they are terrible people.

The villa as social field

The villa as social field

The cynical view towards people’s actions in the villa only takes us so far in because the participants do act in ways that are contrary to their interests. The ‘rules of the game’ — or what Bourdieu would call ‘doxa’ — operate differently, with a much less ‘instrumental’ way of operating. Love Island operates in its own way with a certain honour code that participants mostly follow. Eliminations demonstrate this best, with participants being given ‘second chances’ even when eliminating stronger or more popular participants might give your couple a better chance at winning. Same with the couples themselves: being a better, genuine couple who have the potential to win the programme tends to help avoid elimination by your fellow islanders! And indeed, platonic friendship as much as romantic relationships can help keep you in the villa — despite, well, the ‘love’ part of the game. If you want an insight into how the rules of the game operate — or the honour code of the villa — then just listen to Anton’s monologues during eliminations:

‘The Outside World’

The ‘autonomous’ social fields we talk about with Bourdieu is quite helpful to talk about how social fields work in different ways with different rules and with different stakes (capitals). But ultimately fields are ‘relatively’ autonomous and can act in ‘ homology’ with other social fields — such as more economic or socially powerful fields. So while gaining social capital and building ‘genuine’ relationships form the basis of the competition in the villa, these activities are ultimately directed elsewhere. The hope for these participants is that they can convert their symbolic capital — or ‘genuine’ social capital — into more powerful forms of social capital or gain access to economic capital.

It is important to note that the ‘outside’ ultimately determines who goes into the villa, and to get into the villa you need forms of social capital to begin with. The need to have a certain social media following in order to be selected during the audition process leads to some debate about how real or fake the competition in the villa is. The participants are ultimately archetypes of what Brooke Erin Duffy would call ‘aspirational labour’. The prevalence of modelling and social media influencers in the the jobs prior to coming into the villa are no coincidence, nor is the likely career paths that these participants will try to follow once leaving the villa. But as research into aspirational labour shows, the success in being a social media star often relies on access to forms of capital — whether that is money, taste or social relationships. The fact that ‘shocks’ such as ex-partners entering the villa or messages on Instagram is also not likely a coincidence, but a result of the close social circle these people operate within or the relationships (or celebrity) they can draw upon prior to the villa(Danny Dyer’s daughter, AJ/Tyson Fury’s brother).

That’s my sociological take on Love Island — no one asked for it and no one needed it. Looking forward to boring my students next year for two hours with a lecture on this topic.

Neymar and the symbolic economy of football

Neymar and the symbolic economy of football

Once you get past the eye-watering numbers involved, I think the Neymar transfer is a fascinating story on a number of fronts. Most of these are related to arguments that Neymar is either taking a step back (from the insurmountable heights of Barcelona) or dropping down a league (La Liga to Ligue 1) or that he is simply not worth a net outlay of £400m. I’m not disputing much of this, but I do think there is an interesting symbolic dimension to this which I’ve been trying to write about more generally for the past year. So here’s my thoughts (in all their Bourdieusian glory)…

This transfer is being fought on a number of “playing fields” — both on the football pitch, as well as the geo-political dimension as Simon Chadwick’s recent blog illustrates. I do think that a great deal of this can be explained in terms of a symbolic economy rather than the economic clout of both club and country. If spending £400m on one player isn’t enough of a demonstration, money does not matter — either for the club, the country (Qatar) or the player.

What is at stake is “symbolic capital” — legitimacy, rather than financial clout. In each field a specific logic governs how individuals (and organisations) can accrue symbolic capital. In artistic fields for instance, legitimacy is generally opposed to money — Kings of Leon go from “credible” indie band to stadium fillers, the fans that carried them that far then tend to regard them as “selling out”. The symbolic capital accrued in football is different, and while it can be won in ways without money, symbolic capital can increasingly be tied to economic capital within football clubs.

Symbolic capital can indeed be won and lost on the football pitch. While teams ultimately are attempting to simply win football matches, teams can convert 11 sources of cultural capital (the embodied skills and capacities of footballers) into symbolic capital. can be done through playing the right way (Tiki-taka, attacking football), the romantic stories (Leicester, Roy of the Rovers-style stories), etc. This much is clear based on the reverence that Guardiola enjoys and the revulsion that Sam Allardyce can attract based on how their teams conduct their football.

For PSG, the massive outlay in transfer fees is to attain legitimacy — a transfer of large amounts of economic capital (to purchase forms of embodied cultural capital) in the hope of attaining symbolic capital. Having a player that has large amounts of acclaimed embodied cultural capital can add to a sense of legitimacy to the club. Even the transfer fee, or even the transfer record, can give sense to this being a ‘big club’. The ultimate aim is of course to win the biggest prize in club football, the Champions League, which allows the club to say they are one of the select clubs to win the trophy.

While a lot of people say that Neymar is dropping down a club (Barcelona, tika-taka, more than a club… symbolic capital par excellence), this strategy has been successful for a number of clubs — Manchester City are now seen as a legitimate big club attracting revered managers, Chelsea before them have a Champions League, with both clubs now unquestioned “Top 4” clubs in England rather than viewed as noveau riche. Ultimately, as a Brazilian with designs on winning a Ballon D’Or via a World Cup, the league does not matter at all — league football is increasingly a means to an end: accessing the Champions League (the Top 4 trophy) and getting goal tallies up. La Liga and Ligue 1 are ultimately quite similar in the disproportionate distribution of talent and money at the top. The only reason they are viewed differently is via the co-efficients of European performance. Yet, PSG are already quite comfortably a top 8 team in Europe simply based on their recent Champions League finishes. Indeed, if anything for Neymar a less daunting league (which PSG ultimately have to win back) might help in his quest to be in peak condition for the World Cup.

While it may seem like this is a strategy to win money in the long run — Symbolic capital is of course convertible into economic capital — perhaps the more desirable element of pursuing symbolic capital is its ability to disguise: if you can appear to do the right things, you can avoid the negative sanctions of the symbolic economy when doing questionable things. Barcelona’s economic links to Qatar — the first sponsor on their famously unsponsored shirts — have not ultimately do any harm to their romantic image. Indeed, the Qatari links to Barcelona predate PSG’s, yet this is not really played up in the media storm over Neymar. Qatar’s involvement in this is perhaps to conjure up some symbolic capital to add some legitimacy to their World Cup, as well as their current trade battles, despite the attention drawn to their horrendous labour practices in building the World Cup. The use of sport as a way of whitewashing — or “sportswashing” — a country’s image has been quite evident over the past decade, particularly in F1. The use however of a single player to achieve this is arguably quite new.

It is of course a little more complicated than this quick, broad brush description; but this is my thinking on the Neymar transfer. We will see how it all works out, but as has been said, this is a transfer that is working on several different levels — but there is definitely an urgent non-economic battle being waged.

Dental care profession project: Looking for participants

This research focuses on the dental care provided by dental care professionals and on how their work and wellbeing is affected by governance decisions and commercial pressures.

Description

Dental care is one of the pillars of a healthy population. Most research in dental health has primarily focused on the impact of population dietary habits and lack of knowledge of dental health. This research instead focuses on the unique demands experienced by dentists in the health care profession.

The study is timely and crucial as it interlinks a number of issues affecting the dental care profession. Dentists are professionals that have a primary responsibility of care for the dental health of their patients. Yet the commercial and managerial pressures experienced by dentists, together with issues related to stress and wellbeing in a profession with greater levels of burnout compared to similar forms of work, could present a tension that affects the quantity and quality of dental care provision.

By highlighting professionals’ wellbeing and values, businesses concerns, and care practices through systematic and robust research, appropriate policy solutions, information, and advice can be developed.

Skill and value in professional football

Skill and value in professional football

I’ve been meaning to try and get back blogging for a while, but have been distracted a lot recently. After the really enjoyable Football Collective conference, I really wanted to go into a bit more details about one of the ideas in my talk I was trying to explain while at the conference.

Just before the summer, there was a goal that caused a curious amount of chat and debate within my football friends. Daniel Sturridge scored a great goal for Liverpool in the Europa League final.

During my talk I tried to link labour process theory, Bourdieu and notions of political economy. I have worked with labour process theory for some time and provided me with the building blocks to moving towards sociology. Based on Marx’s work, LPT is predicated on the notion that employers buy in an employee’s capacity to work: not necessarily the work itself. The job of employer’s is therefore to put that ‘labour power’ to work, to extract the maximum amount of value from that capacity. To extract that value, employers direct the labour of employees — they tell them what to do, or set up bureaucracy to control the labour of employees, or even get employees to buy in to the company so that the employees control themselves.

My PhD was an attempt to show that while many of the core propositions of LPT are conceptually useful, LPT doesn’t really consider what ‘value’ is produced in the workplace and what forms ‘labour power’ takes. To illustrate this I examined musicians, and how the apparent conflict between art and commerce is not so much a case of saying no to money, but a case of wanting to make a contribution considered ‘valuable’ in terms of music, but not necessarily something that gives economic value.

In a similar way, I feel labour process theory can make a contribution to understanding football, but again, how it considers value and how this value is produced needs to be reconsidered. Artistic merit is not something that just happens once the work is produced, but is something that is mediated: people decide the work has artistic merit. Likewise, the skills of footballers produce a form of non-economic value but that this is mediated.

Using Bourdieu’s work, I argue that ‘labour power’ can be considered in terms of use and exchange values of the ‘forms of capital’ (see Bourdieu, 1986: the forms of capital, as well as Beverley Skeggs work). The embodied cultural capital — the most directly linked form of capital to the concept of habitus — is generally the labour power that employer’s in football are buying: the capacities to perform the work. The labour of footballers is generally quite expensive, with the highest skilled footballers’ labour power prohibitively expensive to buy (an exchange between cultural capital and economic capital).

Yet when Arsenal fans clamour for a signing every summer — they are not (necessarily) asking for the embodied cultural capital of a highly skilled player. Arsenal fans are are asking for the ‘name’ or reputation that goes with this cultural capital: symbolic capital. Symbolic capital that is considered ‘legitimate’ or the most ‘prestigious’ within the field. So while Arsene has a reputation for developing cheap sources of labour power — e.g. Fabregas — what Arsenal fans are looking for is a reputation for already established skills, and this involves an exchange of economic capital for both cultural and symbolic capitals.

How this reputation is established is on the field: being established as a winner through trophies and awards, goal and assist records, the transfer fee itself, and most importantly, the skills themselves. A moment of genius on the pitch is accorded symbolic capital through the views of fans and observers (what Bourdieu called cultural intermediaries) — it is not automatically accorded value. So while Daniel Sturridge scores, to what many people think, an extraordinary goal, these things are mediated and contested with other fans and observers.

(Another reason I bring up the disagreements over Daniel Sturridge’s goal is another element that is a question I’m still trying to think through: does evaluating the skills of a footballer have to be embodied? By that I mean, when I evaluate a goal, is it based on my own (previous, limited) footballing practice? When I explained my view on Sturridge’s goal, I had to put it in terms of kicking the ball, the outside of the boot, the precision, etc. And how much I appreciate a goal often depends on how far away I can imagine it is from my capacities. That’s probably an unanswerable question for me!)

So, basically my talk was predicated on this notion of symbolic capital being produced. The collective production of symbolic capital — through teams, tactics and style – and the accumulation of this symbolic capital, provided me the links to the wider ‘political economy’. I’m hoping to work through these ideas over the next few years. I found the conference very inspiring, and really hope to maybe collaborate with others in developing these ideas and the methods to research them.